|

The Khabouris Codex

Better Light Scanning Back Used to Create an Unparalleled, High-Resolution Digital Record of a Thousand Year Old Aramaic Canon of the New Testament |

||||

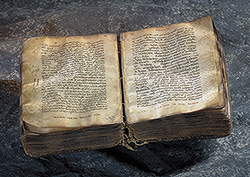

| Visitors to the Queensborough Community College Art Gallery in Bayside, New York, now have an unprecedented opportunity to view the exhibit of an ancient Aramaic New Testament codex that has been carbon-dated to between 1040 and 1090 AD.

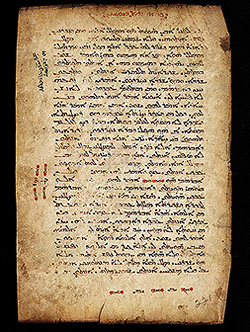

What makes this opportunity particularly compelling is the fact that this manuscript, based on preliminary information gleaned from its colophon page, is a handwritten duplicate of an original canon written as early as 165 AD. If continuing research corroborates this, the Khabouris codex would predate (by more than a century) the oldest known Greek canons of the New Testament, and could provide a more original source of the commonly accepted Aramaic New Testament canon. If its source proves to originate from the third or fourth century, it would still place the codex among the most original New Testament copies in existence today. Included within the Codex pages are the 22 books of the Eastern Orthodox Canon (which excludes the Book of Revelations and the four short Epistles — Jude, II Peter and II and III John). The Khabouris’ colophon bears the seal and signature of the Bishop at the Church at Nineveh, an erstwhile capital of the Assyrian Empire that is the present-day Iraqi city of Mosul. FLATTENING ANCIENT PAGES “At some point water damage had warped the pages,” he said. “A half-inch to three-quarters of an inch variation on a page would require too much depth-of-field for the macro level forensic analysis we had hoped to capture in a single shot. Yes, stitching was considered, but it would have been overwhelmingly difficult to accomplish — considering we were dealing with over 500 pages as well as the introduction of many more complications in the stitching process. Traditionally, the path would be to go through over a year’s processing with conservators flattening the pages by rehydration. It was estimated this process would cost a minimum of $150,000 and would risk losing diacritical marks and further damage to the already water-damaged pages. Then we would still need to photograph the pages”. “I used a microscope to view just how the pages would flex and how the iron gall ink would respond if a page were to be physically flattened”, Rivera continued. “I discovered that because the outside edge of the script was written a half inch to over an inch inside the outer border of the page, the writing on the page was on parchment that was actually much less convoluted than the outside border of the parchment. The amount of flattening the center region of the page would need was much less than the outer edges of a page, and I could indeed selectively flex the page using a very rigid stainless steel plate behind layers of felt sized to match the written area. The parchment would flex flat without flaking or cracking the original ink using a very gentle, gradual amount of force. The iron gall ink was amazingly resilient. The cracks in the script I had seen under the microscope appeared to be due to the natural process of the ink aging and curing over the centuries.” CREATING THE DIGITAL ARCHIVE “I even tested direct flat-bed scanning, but found it risked exposing the pages and the binding of the codex to too much heat or stress, and the resulting image did not produce the macro detail that could be achieved from specialized lenses I could use with film. This threw off my estimates of necessary resolution, and I was back to stitching very large files from flat bed scans. I estimated I would theoretically need over four terabytes of scans and 18 months time! What I did not understand until I actually compared a scan to a photo, was that a larger file size from a scan did not necessarily give a corresponding increase in final detail compared to a better shot from film, and my depth of field requirements made it ultimately untenable.” “I decided to start from the beginning and searched for professional photographers that might have the high-end equipment to digitally capture the codex pages. The project was just overwhelming for most photographers to meet my criterion. With what remained in my personal funds, even if they assured me their equipment was good enough I knew the painstaking effort necessary to set up each page would make it impossible to compensate a professional. I had the right idea in the very beginning, but I was on the wrong side of the universe,” Eric recalled with a laugh. “It was a year before I discovered Better Light’s digital scanning system, and I’m so fortunate that Better Light loved the project and would allow me to work on this at their facilities! Through them I met accomplished photographers like Ben Blackwell and Stephen Johnson, enthusiastic and very helpful Better Light users. This is a family of great people at Better Light. When I finished, my only regret was not having an excuse to work on a daily basis with such gifted people”. Using Better Light’s Super 8K-2 system, it took Eric only a few minutes to do a full resolutionscan of each page. Shortly thereafter, it took even less time with the new hi-speed USB system he used as soon as became available. “Not only was there far less heat on the codex from David Christensen's great NorthLights, I could scan 20 shots in the time it would have taken to complete one traditional flatbed scan. This was a great system for work flow,” Eric said. “You can correct color, adjust lighting, focus, all on the fly. And, because each image is of such high resolution, you can set up a full page shot and the additional steps required from film are unnecessary! We were fortunate to have a lens that resolved just enough macro detail to make this work. We could have gotten even more detail if we had been able to find a lens that could match what the Super 8K can capture”. “Since the pages were carefully flattened, we had maximum sharpness,” he continued. “These images are sharper than anything that I had done before, even with stitching. And these are really big shots... there is so much detail. It's like using a microscope - you can see the fungus and the cracks in the script with great color clarity! There is no question as to whether you’re looking at an original character from a thousand years ago, or an added character from another ink or handwriting.” “Each page took roughly a half hour to an hour to photograph with the Better Light system. The exception was the six loose pages in the manuscript, which took up to two hours apiece, since they had nothing to anchor them. I was determined to be gentle with the codex while creating the absolute best shot I could. The set-up process was painstaking, and I built up muscles as I took the time to perfectly level each page, etc. I had committed myself to making my last shot my best shot,” Eric commented. “The entire project was very challenging since it was so experimental. We worked the lighting endlessly to get as even an illumination as possible. Eventually I could set it up in half the time, but it was a matter of learning and trial and error.” “White light and full color imaging is limited to what the page can reflect in the normal visible light spectrum” Eric said. “Ultraviolet can bring out detail due to how the parchment reacts to it." We discovered that when we filtered out the infrared and blocked all other light sources, we could capture the fluorescence of the parchment from exposure to black light with the Super 6K Monochrome camera (no RGB filters over sensor). The ink does not fluoresce. This made it possible to see the latent text in portions of the parchment where the ink was faded by its relative lack of UV response” [PAGE SAMPLES WITH ULTRAVIOLET ILLUMINATION] It was a pleasant surprise to the team at Better Light to discover that the Super 6K Monochrome camerawas sensitive enough to capture a UV fluorescence image! We added a Wratten #12 Yellow filter to increase the captured contrast of the image. “The Super 6K models have fewer pixels in the same space, so the pixels are larger,” said Robin Myers of Better Light. “Whereas the Super 8K pixels are 9 microns square, the Super 6K pixels are 12 microns square. With the Super 8K you’d have to crank everything up to the roof; the Super 6K simply has more photosensitive area to capture the light. And we needed all the light sensitivity we could get!” Fortunately for the team, the two scan backs are the same basic unit — the same size with the same software. They could easily and quickly swap the two systems. “We needed to create ideal interchangeable camera conditions due to the time constraints I was working under," Eric said. According to both Eric and Myers, these UV images may be the most important of all. Not only do they offer detail that full color cannot, UV is a common technique to detect forgery. The UV images will prove the pages’ authenticity. "If there had been more time, I would have captured the entire codex in UV, but I managed to capture those areas that were most damaged before leaving for New York to deliver the codex.” Myers noted that the codex’s colophon page presented even more challenges. It was the most damaged page in the Khabouris. “Someone had put a burlap-type material on the inside cover, which basically sanded off the colophon page over time,” he said. “To capture a wider range of data in a single image, we tried high-dynamic-range imaging — you set the sensitivity of each CCD row individually. And, we tried colored filters: three to four setups of UV, UV plus visible, infrared, IR plus visible. “We tried combinations, everything to see what would be appropriate,” Myers continued. “We rebuilt the lighting setups four or five times. Finally we got it.” “I think we would find, in the end, that we had the best system for this job,” Eric said. “We’ve got more information than has ever been collected, and it’s more high-resolution than anything collected before. I don’t believe this technology will ever be much improved upon. “Without the generosity of Better Light, I could not have gotten this far,” he added. “They let me use their equipment, and they shared their technical expertise. They were so excited about the project.” “It was a technical challenge,” Myers said. “We have lots of museums and libraries that use our cameras, but we don’t usually get 1,000-year-old documents coming through our door.” “The idea is to protect the codex,” he began. “Researchers and translators can use the digital images for their work, and the manuscript need not be subjected to further handling. Also, until I had completed this work, losing the codex would have meant losing its secrets. Now the codex is safe in more ways than one." Where does Eric, who has funded this entire process, go from here? “From October, 2004 through January my work was on getting the exhibit done,” he said. “Now I’m back to cataloging, researching the next stages and documentation. I am researching the forensic image analysis process and excited about the possibilities of special software for post-processing, as well as software used in the medical imaging field that can make the most of these images. The Khabouris Institute will be a lifelong pursuit from which the codex is the starting point,” he continued. “It is a necessity to develop methods to fund the Khabouris translation, perhaps by offering the 25% resolution images for sale on DVDs which could easily printout the pages at 200% original size. The institute now has an 800 gigabytes resource of images from the months of work at Better Light!” According to Eric, new insights have already emerged from this ancient text from pioneering work done by the late Dan MacDougald, his colleagues, and men like Bishop Gerrit Crawford. “Critical differences have been found that will alter the version of Christianity being taught today,” he said. “With the Khabouris codex, you get closer to the source - providing insights into the original ideas that haven’t been as diluted and confused through time and generations of interpretations and languages. We want to explore these original concepts and make sure we hear them as they were intended.”

Copyright 2004-2007 Better Light, Inc. All Rights Reserved. |

||||